New Jersey Civil Service Testing and Examination Appeals

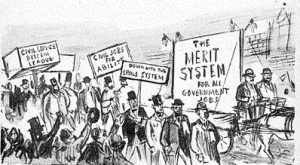

The key to New Jersey Civil Service hiring and promotion is the examination. The State Constitution and New Jersey Civil Service Act require merit-based appointments based, whenever possible, on examinations.

Announcements. The New Jersey Civil Service Commission is responsible for administrating examinations which fairly test applicants’  knowledge, skills and abilities for the job. Announcements are posted on the Commission’s website, and provided by the employer. Announcements include title, salary information, admission qualifications, filing information, and duties and responsibilities. No unannounced requirements can be considered. Applications must be filed by the announced date. The applicant must be a resident of New Jersey and the specified local jurisdiction, unless a different residency requirement is specified or there are not enough available qualified residents. Applicants for municipal law enforcement or firefighter positions must be under 35 for open competitive examinations, except that applicants under 45 may subtract prior law enforcement experience to meet the 35 year age requirement. Veterans may subtract their service from their age to determine eligibility.

knowledge, skills and abilities for the job. Announcements are posted on the Commission’s website, and provided by the employer. Announcements include title, salary information, admission qualifications, filing information, and duties and responsibilities. No unannounced requirements can be considered. Applications must be filed by the announced date. The applicant must be a resident of New Jersey and the specified local jurisdiction, unless a different residency requirement is specified or there are not enough available qualified residents. Applicants for municipal law enforcement or firefighter positions must be under 35 for open competitive examinations, except that applicants under 45 may subtract prior law enforcement experience to meet the 35 year age requirement. Veterans may subtract their service from their age to determine eligibility.

Types of Examinations. Examinations may be written; oral; performance evaluation; physical performance tests; assessment exercises; and evaluation of education, training and experience. The goal is to objectively measure an applicant’s fitness and merit. Thus, while subjectivity in developing an examination is not forbidden, it must be limited.

New Jersey Lawyers Blog

New Jersey Lawyers Blog

processes to ensure that employment decisions are based on merit and fitness, just cause must be found for imposing discipline. And because the employer is the government, all discipline, New Jersey’s Court’s have

processes to ensure that employment decisions are based on merit and fitness, just cause must be found for imposing discipline. And because the employer is the government, all discipline, New Jersey’s Court’s have  government civil service jurisdictions.

government civil service jurisdictions. classifications are.

classifications are. on how the employer chooses to label it.

on how the employer chooses to label it. defined as a suspension or fine of more than five days. Major discipline includes removal, disciplinary demotion, and suspension or fine for more than five working days. The

defined as a suspension or fine of more than five days. Major discipline includes removal, disciplinary demotion, and suspension or fine for more than five working days. The  ivision gave a cogent

ivision gave a cogent  he choice will depend on the relief sought. If the employee does not want to continue working for the employer or does not care about correcting the discipline, but rather only cares about collecting money damages, then she would sue in court (New Jersey state courts and New Jersey law provide greater procedural and substantive advantages for employees, so they usually file in the Superior Court rather than federal court). If the employee is more concerned about getting her job back or correcting the discipline, often the administrative route (which can also provide back pay) is the best choice. When there are no issues of constitutional rights, or discrimination or retaliation, then the administrative route is the only option.

he choice will depend on the relief sought. If the employee does not want to continue working for the employer or does not care about correcting the discipline, but rather only cares about collecting money damages, then she would sue in court (New Jersey state courts and New Jersey law provide greater procedural and substantive advantages for employees, so they usually file in the Superior Court rather than federal court). If the employee is more concerned about getting her job back or correcting the discipline, often the administrative route (which can also provide back pay) is the best choice. When there are no issues of constitutional rights, or discrimination or retaliation, then the administrative route is the only option.